Transposition

In this guide...

Key terms:

Subscription required!

To view the complete study guide, you will need a valid subscription. Why not subscribe now?

Already have a subscription? Make sure you login first!

Introduction

Building on your knowledge of intervals and the different clefs, let's tackle a very important topic: transposition

Transposition

Put very simply, transposition is the process of writing out a piece of music starting on a different note, in a different key, and perhaps with a different clef.

It still remains the same piece of music, but it will sound higher or lower overall, depending on the new starting note.

Transposition happens all the time in music, and being able to tranpose a piece of music is an important skill.

Reasons for transposing

There are many reasons why we transpose music. Here are the two most common reasons:

Ease of performance

Sometimes a piece of music is just a bit too high or too low for us to easily play. This is never a problem for the piano, but it is often a problem for other instrumentalists, and particularly for singers.

Sometimes, even for pianists, a piece of music is in a difficult key, even if the notes themselves are within a comfortable range.

In these situations, we can transpose the music up or down so that the range is comfortable, or so that the key is easy. Every note must be moved up or down by exactly the same interval.

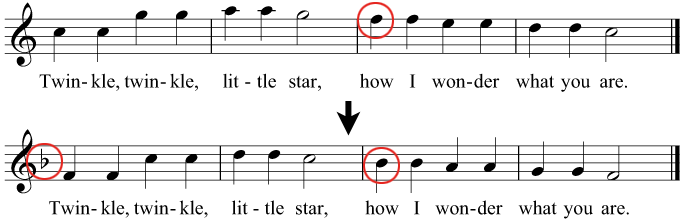

This music looks quite high to sing, so we'll transpose it down by a perfect fifth to make it easier

This music looks quite high to sing, so we'll transpose it down by a perfect fifth to make it easierNote that in this example, the key signature has changed as well as the notes (from C major down to F major: a perfect fifth). This ensures that each note is at the correct pitch - otherwise, those F's would become B naturals and the familiar tune would sound quite wrong!

For different instruments

When you write down a note, you would expect that when a musical instruments plays the note, the same pitches would sound as has been written. This is indeed true for most instruments.

However, some musical instruments (such as the clarinet, the French horn, and the saxophone) read music that is not written at the same pitch at which it sounds. These instruments play at a different pitch from that written.

One simple reason for this might be that the instrument plays very high or very low notes, and so we write the music at a higher or lower pitch so that it is easier to read, but it still sounds at the correct pitch.

When we do this, we need to write the music out to suit the instrument, and to do this, we transpose the original up or down accordingly.

Here is a simple example of this, for the piccolo. This very high-sounding instrument would require constant use of ledger-lines if we wrote the music at concert pitch, so instead, we transpose everything down an octave. When these notes are played, they sound one octave higher, solving the problem of legibility with too many ledger lines.

The piccolo sounds at such a high pitch that we need to write all the notes down an octave lower than they will sound

The piccolo sounds at such a high pitch that we need to write all the notes down an octave lower than they will soundInstruments for which it is necessary to transpose the music are called transposing instruments.

Transposing instruments

When we write down a C, and we expect a C to be heard when the note is played, the note C is described as being in concert pitch. Therefore we can say that a non-transposing instrument such as the violin or piano plays "in concert pitch".

By contrast, when we write down a C, and it is played by a trumpet, the note B flat sounds - a tone too low! Therefore, we have to write that note C up a tone - a D - in order for a C to sound.

We say, in this case, that the trumpet is playing "in B flat" (when it plays a sounding B flat, then a C has been written), and that the trumpet is a tone lower than concert pitch.

This is not to be confused with the key of B flat major - the trumpet could be playing music written in any key, but we say that the instrument itself is "in B flat" because that means it is playing music a tone lower than is written.

Don't worry if this is a little confusing. It can confuse even very experienced musicians, and takes a lot of practice to get used to!

Just try to remember that the "in" pitch of the instrument (e.g., trumpet "in" B flat) is the pitch that would sound when the instrument plays a written C. Knowing this, you can figure out how to write a part for the instrument that will sound at the intended pitch.

We will look at the various instruments that play "in B flat" and some that play "in A" or "in E flat" in Range, transposition, and clefs.

How to transpose

In order to transpose a passage of music, you will need the interval and the direction of transposition.

For example, to transpose music for trumpet in B flat from concert (sounding) pitch to transposed (written) pitch, the interval is a major 2nd (i.e., a tone) and the direction is up.

The basic steps for transposing are as follows:

- Work out the new key for the transposed music. Simply transpose the note-name of the original key signature by the required interval; for example, when transposing up a tone, if the key signature has one sharp, that is G major; so the transposed music will be in A major - three sharps.

- Transpose each note up or down by the correct interval. For example, when transposing down a minor 3rd, an A would become an F sharp.

- Double-check your accidentals. Make sure that you don't repeat an accidental that is already in the key signature, and make sure that you use a cautionary accidental (including naturals) where necessary to ensure that you write down the correct pitch.

- Check again. Check every single note in turn to ensure that it is at the correct interval with respect to the original.

- Check once more. Is every interval between the notes the same in the transposed version as in the original?

- Copy other markings. Make sure that you copy all the markings - phrasings, dynamics, tempo markings, and time signatures - from the original into the transposed version, and make sure that the time value of each note is the same as in the original.

Let's look through these steps with a real example.

Q. The following melody is written for clarinet in A. Transpose it down a minor 3rd, as it will sound at concert pitch. Remember to put in the new key signature and add any necessary accidentals.

Step by step transposition

Step by step transpositionChecklist

We can summarise the steps above in a simple list. It's worth remembering this, perhaps by inventing a mnemonic, if that helps:

- Key (transpose the key)

- Notes (transpose the notes)

- Accidentals (check your accidentals)

- Check (double check all the intervals)

- Markings (copy all markings from the original)

Traps

There are several traps to watch out for when transposing.

Enharmonics

Don't be tempted to use the wrong enharmonic version of a note. For example, when transposing up a perfect fifth, the note B would become F sharp and not G flat. The interval B to G flat is a diminished 6th, not a perfect 5th!

Here is an illustration of this trap, showing an incorrect and correct transposition, in which we are asked to tranpose up by a perfect 5th.

Transpose the music up by a perfect fifth.

Transpose the music up by a perfect fifth.Accidentals

You won't always be asked to use a key signature when transposing, and your approach to accidentals will depend on the presence (or not) of the key signature.

- If there is no key signature, make sure that every note that needs one has an accidental - but don't repeat two accidentals for the same pitch (in the same octave) twice in one bar.

- If there is a key signature, make sure that you don't use an accidental that is also in the key signature unless that accidental has been cancelled previously by another accidental.

- Likewise, if there is a key signature in the original, make sure you observe it, otherwise you could easily assume a note is a B natural, for example, when in fact it is a B flat, and while you might apply the correct interval to B natural, it will be incorrect because the original note was a B flat.

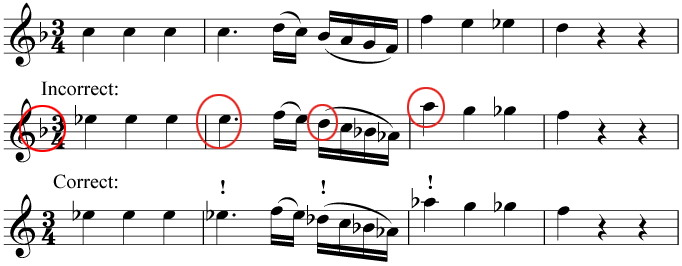

In this example, we are asked to transpose the music up by a minor third, without using a key signature.

Transpose the music up by a minor third.

Transpose the music up by a minor third.Do not use a key signature but remember to put in all necessary sharp, flat or natural signs.

Beam and stem direction

Often, notes in your tranposition will need to change the direction of their stem, or their beam if they are grouped.

- For stems: if a note is on the middle line of the stave or higher, the stem should point down. If the note is below the middle line, the stem points up.

- For notes grouped by beams: always work from the first note of the group. If the first note of a beamed group is on the middle line or higher, the whole group's stems should point down and the beam will be beneath the note-heads. If the first note of a beamed group is below the middle line, then the whole group's stems should point up and the beam will be above the noteheads.

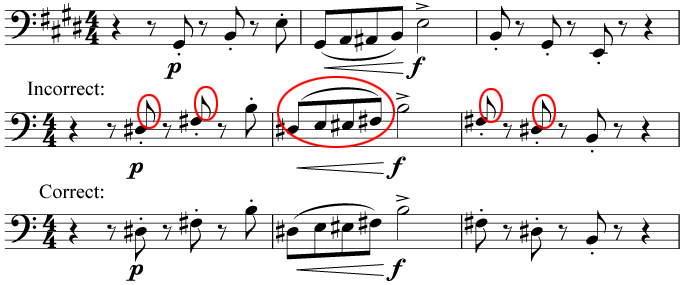

Here is an example showing changes in stem and beam direction as a result of transposition. We are asked to transpose up by a perfect fifth, without using a key signature.

Transpose the music up by a perfect fifth. Do not use a key signature but remember to put in all necessary sharp, flat or natural signs.

Transpose the music up by a perfect fifth. Do not use a key signature but remember to put in all necessary sharp, flat or natural signs.The only mistake in this example was to keep the tails pointing in the same direction as the original, spoiling an otherwise perfect answer!

Double sharps and flats

Sometimes there will be a double sharp or a double flat in the music. After transposing, sometimes the double sharp or flat will become a single sharp or flat, but you must always make sure you keep the same intervals between notes.

Don't be tempted to convert the note into an enharmonic equivalent and thereby change the interval between the notes.

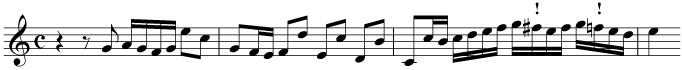

Here is an example (from a fugue by J. S. Bach) showing a problem with a double sharp. In this case we are asked to transpose down by only a semitone, from C sharp major into C major. Perhaps the purpose is to make it easier to play?

This music is in C sharp major. Transpose the music down by a semitone into C major.

This music is in C sharp major. Transpose the music down by a semitone into C major. Did you transpose the double sharp correctly?

Did you transpose the double sharp correctly?Read more...

With a subscription to Clements Theory you'll be able to read this and dozens of other study guides, along with thousands of practice questions and more! Why not subscribe now?

Revision

Are you sure you've understood everything in this study guide? Why not try the following practice questions, just to be sure!